The Future of Jobs Report 2020

Chapter 2. Forecasts for Labour Market Evolution in 2020-2025

Over the past five years, the World Economic Forum has tracked the arrival of the Future of Work, identifying the potential scale of worker displacement due to technological automation and augmentation alongside effective strategies for empowering job transitions from declining to emerging jobs. At the core of the report and its analysis is the Future of Jobs survey, a unique tool which assesses the short- and long-term trends and impact of technological adoption on labour markets. The data outlined in the following chapter tracks technological adoption among firms alongside changing job requirements and skills demand. These qualitative survey responses are further complemented by granular data from new sources derived from privately-held data that tracks key jobs and skills trends. Together, these two types of sources provide a comprehensive overview of the unfolding labour market trends and as well as an opportunity to plan and strategize towards a better future of work.

2.1 Technological adoption

The past two years have seen a clear acceleration in the adoption of new technologies among the companies surveyed. Figure 18 presents a selection of technologies organized according to companies’ likelihood to adopt them by 2025. Cloud computing, big data and e-commerce remain high priorities, following a trend established in previous years. However, there has also been a significant rise in interest in encryption, reflecting the new vulnerabilities of our digital age, and a significant increase in the number of firms expecting to adopt non-humanoid robots and artificial intelligence, with both technologies slowly becoming a mainstay of work across industries.

These patterns of technological adoption vary according to industry. As demonstrated in Figure 19, Artificial intelligence is finding the most broad adaptation among the Digital Information and Communications, Financial Services, Healthcare, and Transportation industries. Big data, the Internet of Things and Non-Humanoid Robotics are seeing strong adoption in Mining and Metals, while the Government and the Public Sector industry shows a distinctive focus on encryption.

Note: AGRI = Agriculture, Food and Beverage; AUTO = Automotive; CON = Consumer ; DIGICIT = Digital Communications and Information Technology; EDU = Education; ENG = Energy Utilities & Technologies; FS = Financial Services; GOV = Government and Public Sector; HE = Health and Healthcare; MANF = Manufacturing; MIM = Mining and Metals; OILG = Oil and Gas; PS = Professional Services; TRANS = Transportation and Storage.

These new technologies are set to drive future growth across industries, as well as to increase the demand for new job roles and skill sets. Such positive effects may be counter-balanced by workforce disruptions. A substantial amount of literature has indicated that technological adoption will impact workers’ jobs by displacing some tasks performed by humans into the realm of work performed by machines. The extent of disruption will vary depending on a worker’s occupation and skill set.33

Data from the Forum’s Future of Jobs Survey shows that companies expect to re-structure their workforce in response to new technologies (Figure 20). In particular, the companies surveyed indicate that they are also looking to transform the composition of their value chain (55%), introduce further automation, reduce the current workforce (43%) and expand their workforce as a result of deeper technological integration (34%), and expand their use of contractors for task-specialized work (41%).

The reallocation of current tasks between human and machine is already in motion. Figure 21 presents the share of current tasks at work performed by human vs. machine in 2020 and forecasted for 2025 according to the estimates and planning of senior executives today. One of the central findings of the Future of Jobs 2018 Report continues to hold—by 2025 the average estimated time spent by humans and machines at work will be at parity based on today’s tasks. Algorithms and machines will be primarily focused on the tasks of information and data processing and retrieval, administrative tasks and some aspects of traditional manual labour. The tasks where humans are expected to retain their comparative advantage include managing, advising, decision-making, reasoning, communicating and interacting.

2.2 Emerging and declining jobs

Extrapolating from the figures shared in the Future of Jobs Survey 2020, employers expect that by 2025, increasingly redundant roles will decline from being 15.4% of the workforce to 9% (6.4% decline), and that emerging professions will grow from 7.8% to 13.5% (5.7% growth) of the total employee base of company respondents. Based on these figures, we estimate that by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, while 97 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms, across the 15 industries and 26 economies covered by the report.

The 2020 version of the Future of Jobs Survey also reveals similarities across industries when looking at increasingly strategic and increasingly redundant job roles. Similar to the 2018 survey, the leading positions in growing demand are roles such as Data Analysts and Scientists, AI and Machine Learning Specialists, Robotics Engineers, Software and Application developers as well as Digital Transformation Specialists. However, job roles such as Process Automation Specialists, Information Security Analysts and Internet of Things Specialists are newly emerging among a cohort of roles which are seeing growing demand from employers. The emergence of these roles reflects the acceleration of automation as well as the resurgence of cybersecurity risks.

In addition, as presented in the Industry Profiles in Part 2 of this report, a set of roles are distinctively emerging within specific industries. This includes Materials Engineers in the Automotive Sector, Ecommerce and Social Media Specialists in the Consumer sector, Renewable Energy Engineers in the Energy Sector, FinTech Engineers in Financial Services, Biologists and Geneticists in Health and Healthcare as well as Remote Sensing Scientists and Technicians in Mining and Metals. The nature of these roles reflects the trajectory towards areas of innovation and growth across multiple industries.

At the opposite end of the scale, the roles which are set to be increasingly redundant by 2025 remain largely consistent with the job roles identified in 2018 and across a range of research papers on the automation of jobs.34 These include roles which are being displaced by new technologies: Data Entry Clerks, Administrative and Executive Secretaries, Accounting and Bookkeeping and Payroll Clerks, Accountant and Auditors, Assembly and Factory Workers, as well as Business Services and Administrative Managers.

Such job disruption is counter-balanced by job creation in new fields, the ‘jobs of tomorrow’. Over the coming decade, a non-negligible share of newly created jobs will be in wholly new occupations, or existing occupations undergoing significant transformations in terms of their content and skills requirements. The World Economic Forum’s Jobs of Tomorrow report, authored in partnership with data scientists at partner companies LinkedIn and Coursera, presented for the first time a way to measure and track the emergence of a set of new jobs across the economy using real-time labour market data.35 The data from this collaboration identified 99 jobs that are consistently growing in demand across 20 economies. Those jobs were then organized into distinct professional clusters according to their skills similarity.

This resulting set of emerging professions reflects the adoption of new technologies and increasing demand for new products and services, which are driving greater demand for green economy jobs, roles at the forefront of the data and AI economy, as well as new roles in engineering, cloud computing and product development. In addition, the emerging professions showcase the continuing importance of human interaction in the new economy through roles in the care economy; in marketing, sales and content production; as well as roles where a facility or aptitude for understanding and being comfortable working with different types of people from different backgrounds is critical. Figure 23 displays the set of roles which correspond to each professional cluster, organized according to the scale of each opportunity.36 Due to constraints related to data availability, the Care and Green Jobs cluster are not currently covered by the following analysis.

Note: Job transitions refers to any job transition while job pivots refers to individuals moving away from their current occupation. Job Families are groups of occupations based upon work performed, skills, education, training, and credentials. Data derived from the following countries: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and United States.

In this report we present a unique extension of this analysis which examines key learnings gleaned from job transitions into those emerging clusters using LinkedIn data gathered over the past five years. For this analysis the LinkedIn data science team analysed the job transitions of professionals who moved into emerging jobs over the period of 2015 to 2020. The researchers analysed when professionals transitioned into any new role as well as when they transitioned to a wholly new occupation—here called ‘pivots’. To understand the skill profile of each occupation, analysts first identified a list of the most representative skills associated with an occupation, based on LinkedIn’s Skills Genome Metric which calculates the ‘most representative’ skills across roles, using the TF-IDF method. To examine the extent to which certain skills groups of interest are associated with a particular occupation, a ‘skill penetration’ figure is calculated. This indicates the share of individual skills associated with that occupation that belong to a given skill group. To understand the skill profile of each occupation, analysts calculated the ‘skill penetration’ score for each skill associated with an occupation. That is, the ‘skill penetration’ figure indicates the individuals from that occupation who list the specific skill as a share of all individuals employed in that occupation.

The aggregate skills similarity between two occupations is then calculated as the cosine similarity of those two occupations. In addition, for each skill group, a skills gap measure is calculated by expressing the skill penetration of the destination job as a share of the same indicator in the source job.

The evidence indicates that some emerging job clusters present significant opportunities for transitions into growing jobs (jobs in increasing demand) through effective career pivots. As demonstrated in Figure24 A, among the transitions into Data and AI professions, 50% of the shifts made are from non-emerging roles. That figure is much higher at 75% in Sales, 72% in content roles and 67% of Engineering roles. One could say that such field are easier to break into, while those such as Data and AI and People and Culture present more challenges. These figures suggest that some level of labour force reallocation is already underway.

By analysing these career pivots—instances where professionals transition to wholly new occupations—it becomes apparent that some of these so-called ‘jobs of tomorrow’ present greater opportunities for workers looking to fully switch their job family and therefore present more options to reimagine one’s professional trajectory, while other emerging professions remain more fully bounded. As presented in Figure 24 C only 19 % and 26% of job transitions into Engineering and People and Culture, respectively, come from outside the job family in which those roles are today. In contrast, 72% of Data and AI bound transitions originate from a different job family and 68% of transitions into emerging jobs within Sales. As illustrated in Figure 25 emerging job clusters are typically staffed by workers starting in a set of distinctive job families, but the diversity of those source job families varies by emerging profession. While emerging roles in Product Development draw professionals from a range of job families, emerging roles in People and Culture job cluster typically transition from the Human Resources job family. The emerging Cloud Computing job cluster is primarily populated by professionals transitioning from IT and Engineering.

Finally, a number of jobs of tomorrow present greater opportunities to pivot into professions with a significant change in skills profile. In Figure24 B it is possible to observe that transitions into People and Culture and into Engineering have typically been ones with high skills similarity while Marketing and Content Development have been more permissive of low skills similarity. Among the emerging professions outlined in this report, transitions into Data and AI allow for the largest variation in skills profile between source and destination job title.

Figure 25 demonstrates that the newer emerging professions such as Data and AI, Product Development and Cloud Computing present more opportunities to break into these frontier fields, and that, in fact, such transitions do not require a full skills match between the source and destination occupation. However, some job clusters of tomorrow remain more ‘closed’ and tend to recruit staff with a very specific skill set. It is not possible to observe whether those limitations are necessary or simply established practice. It may be the case that such ‘siloed’ professional clusters can be reinvigorated by experimentation with relaxing the constraints for entry into some emerging jobs alongside appropriate reskilling and upskilling.

2.3 Emerging and declining skills

The ability of global companies to harness the growth potential of new technological adoption is hindered by skills shortages. Figure 26 shows that skills gaps in the local labour market and inability to attract the right talent remain among the leading barriers to the adoption of new technologies. This finding is consistent across 20 of the 26 countries covered by the Country Profiles presented in Part 2 of the report. In the absence of ready talent, employers surveyed through the Future of Jobs Survey report that, on average, they provide access to reskilling and upskilling to 62% of their workforce, and that by 2025 they will expand that provision to a further 11% of their workforce. However, employee engagement into those courses is lagging, with only 42% of employees taking up employer-supported reskilling and upskilling opportunities.

Skills shortages are more acute in emerging professions. Asked to rate the ease of finding skilled employees across a range of new, strategic roles, business leaders consistently cite difficulties when hiring for Data Analysts and Scientists, AI and Machine Learning Specialists as well as Software and Application Developers, among other emerging roles. While an exact skills match is not a prerequisite to making a job transition, the long-term productivity of employees is determined by their mastery of key competencies. This section of the report takes stock of the types of skills that are currently in demand as well as the efforts underway to fill that demand through appropriate reskilling and upskilling.

Note: Cross-cutting skills are those skills that are applicable and easily transferable across many occupations and roles.

Note: The gap measure has been capped at 1.00.

Note: The gap measure has been capped at 1.00.

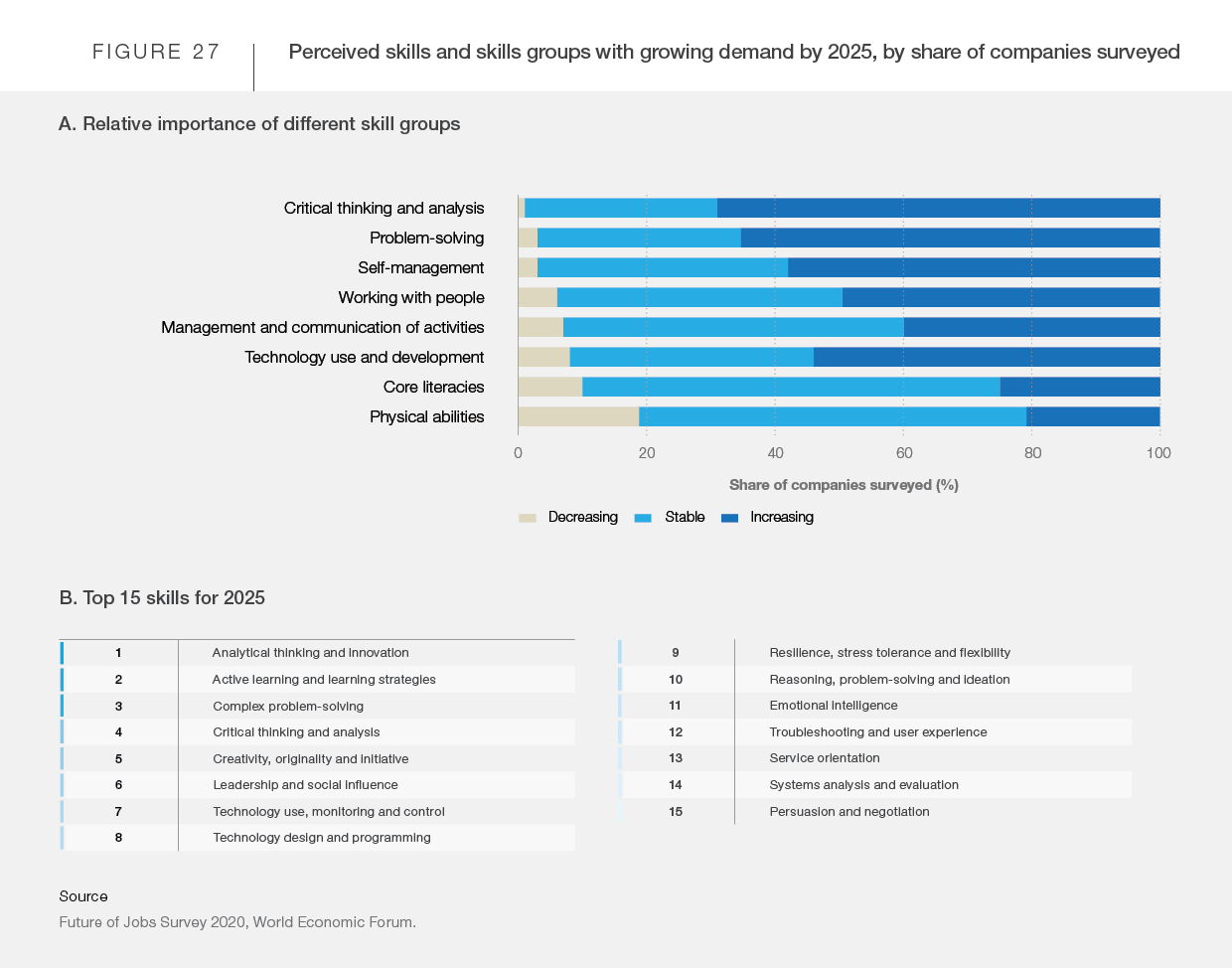

Since its 2016 edition, this report has tracked the cross-functional skills which are in increasing demand. Figure 27 shows the top skills and skill groups which employers see as rising in prominence in the lead up to 2025. These include groups such as critical thinking and analysis as well as problem-solving, which have stayed at the top of the agenda with year-on-year consistency. Newly emerging this year are skills in self-management such as active learning, resilience, stress tolerance and flexibility. In addition, the data available through metrics partnerships with LinkedIn and Coursera allow us to track with unprecedented granularity the types of specialized skills needed for the jobs of tomorrow. Figure 28 demonstrates the set of skills which are in demand across multiple emerging professions. Among these ‘cross-cutting’ skills are specialized skills in Product Marketing, Digital Marketing and Human Computer Interaction.

This report reveals in further granular detail the types of insights that can guide job transitions through to appropriate reskilling and upskilling. Figures 29 and 30 demonstrate those metrics. Figure 29 presents the set of high-growth, emerging roles that are currently covered by the Data and AI job cluster, and the typical skills gap between source and destination professions when workers have moved into those roles over the past five years. Figure 30 presents the typical learning curriculum of Coursera learners who are targeting a transition into Data and AI and the distance from the optimal level of mastery in the relevant job cluster, and quantifies the days of learning needed for the average worker to gain that level of mastery. Figure 29 and 30 together demonstrate that it is common for individuals moving into Data and AI to lack key data science skills—but that individuals seeking to transition into such roles will be able to work towards the right skill set through mastery of skills such as statistical programming within a recommended time frame, in this case, 76 days of learning.

In addition to skills that are directly jobs-relevant, during the COVID-19 context of 2020, data from the online learning provider Coursera has been able to identify an increasing emphasis within learner reskilling and upskilling efforts on personal development and self-management skills. This echoes earlier findings on the importance of well-being when managing in the remote and hybrid work: demand for new skills acquisition has bifurcated. Figure 31 A illustrates the changing demand for training by employment status, comparing the April-to-June period this year with the same period last year. This data reveals a significant increase in demand for personal development courses, as well as for courses in health, and a clear distinction between those who are currently in employment and those who are unemployed. Those in employment are placing larger emphasis on personal development courses, which have seen 88% growth among that population. Those who are unemployed have placed greater emphasis on learning digital skills such as data analysis, computer science and information technology. These trends can be observed in more granular detail in Figures 31 B and C. In particular, self-management skills such as mindfulness, meditation, gratitude and kindness are among the top 10 focus areas of those in employment in contrast to the more technical skills which were in-focus in 2019. In contrast, those who are unemployed have continued to emphasize skills which are of relevance to emerging jobs in Engineering, Cloud Computing, Data and AI.37

When it comes to employers providing workers with training opportunities for reskilling and upskilling, in contrast to previous years, employers are expecting to lean more fully on informal as opposed to formal learning. In the Future of Jobs Survey, 94% of business leaders report that they expect employees to pick up new skills on the job, a sharp uptake from 65% in 2018. An organization’s learning curricula is expected to blend different approaches—drawing on internal and external expertise, on new education technology tools and using both formal and informal methods of skills acquisition. According to data from the Future of Jobs Survey, formal upskilling appears to be more closely focused on technology use and design skills, while emotional intelligence skills are less frequently targeted in that formal reskilling provision. Data from Coursera showing the focus areas of workforce recovery programmes and employer-led reskilling and upskilling activities confirms that finding. In-focus courses are primarily those in technical skills alongside a cohort of managerial skills in strategy and leadership.

On average, respondents to the Future of Jobs Survey estimate that around 40% of workers will require reskilling of six months or less. That figure is higher for workers in the Consumer industry and in the Health and Healthcare industry, where employers are likely to expect to lean on short-cycle reskilling. The share of workers who can be reskilled within six months is lower in the Financial Services and the Energy sectors, where employers expect that workers will need more time-intensive reskilling. These patterns are explored more deeply in the Industry Profiles in Part 2.

According to Future of Jobs Survey data, employers expect to lean primarily on internal capacity to deliver training: 39% of training will be delivered by an internal department. However, that training will be supplemented by online learning platforms (16% of training) and by external consultants (11% of training). The trend towards the use of digital online reskilling has accelerated during the restrictions on in-person learning since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. New data from the online learning platform Coursera for April, May and June of 2020 (quarter 2) signals a substantial expansion in the use of online learning. In fact, there has been a four-fold increase in the numbers of individuals seeking out opportunities for learning online through their own initiative, a five-fold increase in employer provision of online learning opportunities to their workers and an even more extensive nine-fold enrolment increase for learners accessing online learning through government programmes.

Through focused efforts, individuals could acquire one of Coursera’s top 10 mastery skills in emerging professions across People and Culture, Content Writing, Sales and Marketing in one to two months. Learners could expand their skills in Product Development and Data and AI in two to three months and if they wish to fully re-pivot to Cloud and Engineering, learners could make headway into that key skill set through a 4-5 month learning programme.38 Such figures suggest that although learning a new skill set is increasingly accessible through new digital technologies,to consolidate new learning, individuals will need access to the time and funding to pursue such new career trajectories. LinkedIn data presented in section 2.2 indicates that although many individuals can move into emerging roles with low or mid skills similarity, a low-fit initial transition will still require eventual upskilling and reskilling to ensure long term productivity.