The web is ‘fragile.' How to protect the world’s information - and how crypto can help

Most of the world’s information is stored digitally in a way that’s vulnerable to disappearing without warning thanks to everything from link rot and server changes, to someone not paying their web hosting bill. Some information might even disappear because bad actors have removed or changed it. Civil liberties lawyer and Filecoin Foundation president Marta Belcher explains why the modern standard for how we store information is so vulnerable and why protecting data is a human rights issue. She breaks down a fundamentally new approach (leveraging crypto and decentralized databases to protect information and create new incentives to store it) and how it serves as a sneak peek at how Web3 technologies could bake in new approaches to privacy and civil liberties protections. She’ll share how it’s already being used to protect digital artifacts such as Ukraine war crime evidence and Alexander Graham Bell’s earliest sound recordings, and how it could even be used to improve space communications. Marta, a crypto law pioneer, also shares unique ways she’s driven open-source solutions throughout her life and career and how these lessons can help any leader better collaborate.

ポッドキャスト・トランスクリプト

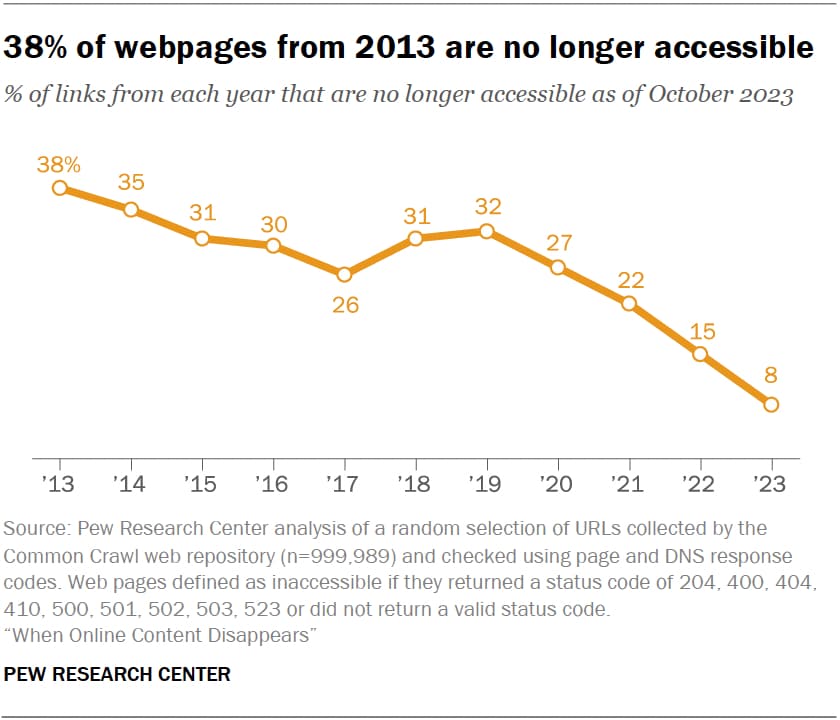

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation: So much information in today's world is digital, right, is stored digitally. But you know if you go to, for example, a Supreme Court brief or a Supreme court decision and there's a link, you now, let's say in the citations, over 50 percent of the time, that link is now broken, which is a huge problem.

If you go to a New York Times article, and a New York Times article has a link, over, I think, 25% of the time, that link has broken. So what that means is that there's a huge amount of data that's lost and a huge number of context that's lost, and that is a problem that I think people don't really think about the magnitude of, but it's a problem for preserving information.

Fundamentally the issue is that the overall architecture of the web is such that when you go to a URL, you're actually looking not for a particular piece of content, but what you're doing is you're going to a particular location in a particular server in a place in the world. And if that data isn't there anymore, it's not there.

And there are many reasons that data could disappear. Someone could delete it intentionally, someone could stop paying their Amazon Web services bill.

It's really important to be able to preserve information even when there are people in the world who might want that information to be gone. For example, testimony of genocide survivors, right? Evidence of war crimes. Climate data, right? All examples of the type of data that many people in the world might want gone, right? And if you have a sort of Internet architecture that really is relying on these single points of failure, it's very easy for that information to disappear.

It's wild to think about, really, in a world where so much of our lives is online, how much of that information can just disappear without us even knowing.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader: Welcome to Meet the Leader. I'm Linda Lacina, and I am very excited to welcome you here to the New York studios here at the World Economic Forum for a very important conversation. Something we don't talk about nearly enough. The web and just how damn fragile it is.

Have you ever clicked a link I've gotten an error message. That dreaded 404 not found. It is so common we often don't even think about it, but it's a reminder that the internet, our standard for storing our most important information, our photos, our music, our memories, our scientific research, our government data, is actually a lot more vulnerable than we often understand.

Sometimes when things disappear, it's because a cloud service has gone defunct or yet another newspaper has closed down. Sometimes, things are deliberately deleted. Confusion, or even to hide a crime.

At the root of all of this is the weaknesses of a centralized web. To tell us more about this, we have Marta Belcher. Marta is a civil rights lawyer, a blockchain law pioneer, and the president of Filecoin, the world's largest decentralized storage network.

She's also the founder of the Filecoin Foundation. That is a non-profit leveraging a special blockchain-powered ecosystem for preserving everything from Smithsonian artifacts to war crime evidence. She's going to talk about what's needed to keep work like this going, especially in an increasingly fragmented world. Thank you so much, Marta, for being here. How are you?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation: I'm fantastic. Thank you so much for having me, Linda.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Well, I want to get started. Let's level the playing field for people. The centralized web, you're going to give us a little bit of a picture between the centralized and the decentralized web. The centralized, how good is it doing at storing the world's information? Can you give it a grade?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I think it would be a pretty low grade, even though I think I'm an easy grader. I think when you think about today's information, if you go to a website, almost always that website is being stored, that data is being stored by one of just three companies, which is Amazon, Microsoft, or Google.

And so what that means is that we're sort of living our daily lives through just a handful of corporations. And we have no choice but to trust those corporations with our data. And it also means that the web is very fragile. We'll often see an outage, like an AWS, Amazon Web Services outage. And then suddenly these vast stores of the web are down for hours. And that really shows really the difficulty with having these single points of failure.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader The Filecoin Foundation did a really, really interesting study last year, and it was called the Not Your Parents Web Study. It looked at 23 million URLs over like 26 years, so this huge swath of the internet history. Can you tell us a little bit about that and sort of what you guys discovered?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation What we discovered, and which is something that I think a lot of other people have discovered as well, is that actually when you look at the web, such a huge portion of it is just gone, right? And so much information in today's world is digital, right, is stored digitally. But you know if you go to, for example, a Supreme Court brief or a Supreme court decision and there's a link, you now, let's say in the citations, over 50 percent of the time, that link is now broken, which is a huge problem.

If you go to a New York Times article, and a New York Times article has a link, over, I think, 25% of the time, that link has broken. So what that means is that there's a huge amount of data that's lost and a huge amount of context that's lost, and that is a problem that I think people don't really think about the magnitude of, but it's a problem for preserving information.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader There was a really interesting statistic from that study that said that most links that are deep links, so not the main URL, but something that's deep into a website, might only have a lifespan of 18 months or less.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation That's right. Yeah, it's wild to think about, really, in a world where so much of our lives is online, how much of that information can just disappear without us even knowing.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader If we were going to define this topic of link rot, why does it happen and why is it really important for us to be understanding?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, so link rot is exactly the problem that I've been describing, which is that you go to a link and often it's just gone. And the reason for that is that the way that today's web works is a particular data, a piece of data, is being stored in a particular location. And there are many reasons that data could disappear. Someone could delete it intentionally, someone could stop paying their Amazon Web services bill.

And fundamentally the issue is that the overall architecture of the web is such that when you go to a URL, you're actually looking not for a particular piece of content, but what you're doing is you're going to a particular location in a particular server in a particular place in the world. And if that data isn't there anymore, it's not there.

So I like to analogize it a little bit to imagine that you just read a really good book. And instead of just telling me the title of the book, what you do is you say, "Well, Marta, you should really read this book. It's in the New York Public Library on the third floor, second shelf from the left, three shelves up, three books over." You tell me the location of the data.

I'm going to go to that location and I have to actually get there and I see if it's still there. But maybe someone took it. Maybe someone ripped a page out. You know, maybe it's just not there at all. And so that's really not an efficient way or a sort of useful way to retrieve information.

And so the technology that I work on is fundamentally shifting how we store information, which is instead of saying go to this particular location for the information, go to a particular server in a particular place, it says look for a piece of content. So every piece of content has a content ID. And you pull that content from wherever it's available. So if it's a available in 100 different places around the world, as long as one of those, even if 99 have failed, as long as one as one is there, it'll pull it. And so that's just a fundamentally different architecture that is a much more resilient architecture than the way that today's web works.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And why is this so surprising? Clearly, we've all had this experience where a link has disappeared, to the point where we just take it for granted. But why is it still such a surprise that this stuff is eroding like it is?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, you know, I think we just sort of take it for granted. There is a nonprofit that we work with a lot called the Internet Archive. The Internet Archive has a thing called the Wayback Machine, where it actually sort of goes in and takes a copy of websites all over the web, right? And this is I think one of the sort of most underrated nonprofits out there, because what it is doing is, you know, truly, truly. one of a kind and absolutely critical for being able to preserve information into the future. But I think, otherwise, you know, aside from the Internet Archive, there really aren't other efforts, a ton of other efforts to do that, and I think it's just something that we kind of take for granted and haven't really thought about. But we're thinking about it.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And as a civil rights attorney, what is the problem? Why is this a big deal? Why should we be tackling this? Why is it so important for society to have information that we can trust, that we find that's reliable?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, so I think there are a number of things that really relate to civil liberties here.

So the first is it's really important to be able to preserve information even when there are people in the world who might want that information to be gone. So for example, testimony of genocide survivors, right? Evidence of war crimes, climate data, right. All examples of the type of data that many people in the world might want gone, right? And if you have a sort of Internet architecture that really is relying on these single points of failure, it's very easy for that information to disappear. And so for us, it is really important that that data is able to be stored in a way where there are many copies all over the world in different jurisdictions and different places. And so we've worked with many different organizations and many organizations have independently used our technology to store humanity's most important information, which is our mission. Because we think it's so important that when there is data that might otherwise disappear, that you're able to store it with a different architecture that will enable it to persist, even if someone wants it gone.

It's really important to be able to preserve information even when there are people in the world who might want that information to be gone.

”Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And you talked a little bit about the technology. Can you tell us a little about how blockchain kind of fits into it?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation So what cryptocurrency does, and cryptocurrency is sort of one use of blockchain, is it lets you write computer programs for your money. So for example, you could write a computer program that says for every second of a song that I play on my computer, automatically transfer one one millionth of a cent from me to the songwriter and from me the singer. And that can happen instantly and automatically across the world. Which is really actually an incredible technology, right? You're really doing for value what the internet, what email did for information, right, being able to send money across the world as easy as an attachment to an email.

So what that does, that ability to program your money basically allows you to, for our technology, write a computer program that creates a decentralized version of the web. There are incentives for people to make sure data becomes available.

So more specifically, what Filecoin is, and Filecoin is the technology that I work on, is a decentralized version of the web, where instead of storing your data with a few companies, people all over the world contribute extra computer hardware to store other people's files. Which means you can have many copies of files all around the world. And the way that it works is cryptocurrency allows us to write a program that says, okay, I'm storing a file on someone else's computer hardware. Check and see if it's still there. And if it is still there, automatically transfer one Filecoin from me to them. And then check again in an hour. And then check again an hour later. And what that does is allows you to create incentives where people are financially incentivized to actually store other people's files. And that means you can create an alternative to Amazon Web Services or Google or Microsoft where people actually are in control of their own data. And so that's how cryptocurrency factors into it.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And how the Filecoin Foundation, how is it different than maybe how other organizations that do something similar approach this?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, so Filecoin Foundation is the governance body for the Filecoin network. So Filecoin is an open-source technology. There are developers all around the world, there are storage providers all around the world and users all around the world. And as an open source technology, it requires sort of open source governance in the same way that any other open source technology has kind of a governance body. So at Filecoin Foundation, you know, it's not like sort of a standard, you know, technology company where. You know, all the technology is being developed in-house. Rather, we are just the governance body for this huge community of developers that is far beyond our organization that are all working on this open source technology.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader There's different players who are coming to protect different types of information, how do they all work within the ecosystem?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin FoundationYeah, so it's really amazing. I think for us, there are all sorts of different stakeholders in our ecosystem. So we have storage providers. And those could be anything from really small operations, even individuals, to massive businesses. And all of them are contributing their computer hardware, their storage space to the network. But they can do that in all sorts of different ways. So we have all sorts of different storage providers. We also have a lot of applications that are building on top of Filecoin and Filecoin is very much sort of this, you know, base layer technology and there are dozens and dozens of applications that use Filecoin sort of under the hood. And so we have all sorts of applications and teams building those. We have developers who are actually developing the technology. So it's just a wide range of community stakeholders. And as Filecoin Foundation, our goal is to really support the broader community.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And when we're talking about preserving the world's most valuable information, give us a couple examples. There's a really interesting initiative you guys have with the Smithsonian. Tell us about that.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation We have tons of really important data that is already being stored on the Filecoin network. So the Smithsonian is one example. The Smithsonian is storing some data on the Filecoin network, specifically it's digitized audio recordings that are historical audio recordings that are being stored in the Filecoin network. We have the USC Shoah Foundation. Stores its genocide survivor testimony on the Filecoin network. We have evidence of war crimes in Ukraine that was actually submitted to the International Criminal Court that's stored on the Filecoin network and the thing that is cool about that is not only do you have that information being stored on Filecoin and preserved and not being able to be deleted, but you also have the ability to cryptographically prove that it was never tampered with. So that's another example of where this technology can be very helpful from a human rights and civil liberties perspective.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And when we talked earlier about how surprising just the disappearance of this information is, this element that disappearing information creates a human rights issue. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation For any kind of human rights issue, it's critical to document the human rights violations. And so there are many, many different organizations that are using the Filecoin network to both ensure that the information that they're capturing is preserved, but also to cryptographically verify that it was never tampered with. So some organizations that we've partnered with or that have built on top of our technology include things like WITNESS, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, an organization called HRDAG that does sort of human data about human rights violations. They all see the benefit of being able to store information with this new technology, this new architecture so that it isn't in a centralized place where it, you know, is really at risk.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader There's lots of things happening online, especially even with the United States. The government has started to preen certain research pieces and maybe other files from other agencies. How does this sort of impact your work and maybe how you guys are thinking about data preservation.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah. So for many years, the Filecoin Foundation has been a big supporter of the Internet Archive's end-of-term crawl, which isn't about one particular political party. It's really at the end of any kind of administration, you have website turnover. And so since 2008, the Internet Archive has actually gone through government websites and made sure that the data is preserved before the next administration comes in. So we've been a huge supporter of that work.

We also have partnered with the Internet Archive on a initiative that we've had for the last few years called Democracy's Library. And that, similarly, the goal of Democracy's library is to take government data from around the world and to preserve it in perpetuity on the Filecoin Network. And so Democracy's Library has worked with many different governments in many different places, including the United States and other countries around the world, to make sure the government data is being preserved and is accessible for the public into the future.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader If a government or an organization is preening information from the internet, what sort of questions does that raise that anybody can be considering and thinking about if they just want to maybe kind of think more deeply about this topic?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I mean, I think it really raises questions about, you know, what does it mean for information to be stored digitally, and what does mean for us to live our lives through just a handful of corporations, right? Because in reality, regardless of whether someone is intentionally deleting data or whether data is just being deleted for other reasons, just not being maintained, You know, it really is a big problem. We really live our lives through just a few corporations and we have no choice but to trust them with our data. And we really have a situation where if one company decides that they don't want that data to be online, it's not online anymore. Or, for that matter, if they decide that they want to give your information to someone else, right? Whether that's, for example, a government that's making a request, right. Because our information is stored by these centralized services, where we're not in control of it, we really have no choice but to trust them to protect our data, to safeguard our civil liberties. I think it's a question of whether we want to trust the companies to do that.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader You guys have a really interesting initiative, one that you would help to spearhead. Can you tell us about the Interplanetary File System?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, absolutely. So when I talked earlier about the idea that data is stored in this way where it's in a particular location on a particular server. I described how you instead could store data such that there's a particular content ID, so any piece of content. You can go and look for that content and just pull it from wherever is closest. That's how IPFS, the Interplanetary File System, works. And IPFS is fundamentally the storage layer that underlies Filecoin. So you have IPFS, which is the decentralized file storage system, and then you have Filecoin built on top of it, which the incentive layer that pays people to ensure that data is stored on the network. So these are sort of two pieces of the same technology.

But one thing that's really interesting is that when IPFS was named the Interplanetary File System. It was actually named that because the technology actually is a much better architecture for doing very, very long distance networking, including networking in space.

So one of my favorite projects that we've worked on was a partnership with Lockheed Martin where we actually built an implementation of IPFS and deployed it in space on a demo mission to really show how IPFS can help with space architecture. And the reason that it is a much better architecture for networking in space is if you have to go a very long distance and you're on sort of today's web where you're looking for data in a particular location and let's say you're looking for it on a server on Earth, then there's going to be a huge delay every time you're getting that data. If you're, say, on the moon or if you're an orbiting satellite or if your out on Mars, right, there's gonna be a multi-minute or multi-second delay every time you want to get that data.

So it makes much more sense instead of going back and forth. To a particular location to have an architecture where you say, OK, I want this piece of content. Please pull this content from wherever it's closest. And it can pull it from, let's say, your own device already has it, or maybe a nearby lunar station, or may be a passing satellite, wherever it is closest it will pull it there. So it's just a much faster way of doing networking.

And it's also a better way of networking for another reason, which is that one of the big problems with storing data in space is that it gets corrupted very easily because of the radiation. So it's much better rather than having a piece of data stored and have it be corrupted and get an error message when you try to retrieve it, it's must better to be able to have 10 copies of it and then just say, I'm looking for this piece of content, and even if nine of them are corrupted, as long as one of them isn't, it'll still serve you that content. So it is just a much better architecture for space.

In addition to that, it also, as I've mentioned, allows you to cryptographically prove that data wasn't tampered with. That's how the technology works. Which is very cool for things like, you know, satellite images, for example, right? So those are the reasons that, you know, we really think that IPFS is a really great architecture to use for the future of networking in space.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And as we're looking to pursue decentralized solutions to protecting information, what else is needed, right? Say one of the goals that the organization has is like, let's get rid of any existing pain points. What does that look like? What else needs to be tackled to make sure that we can protect information going forward? If you had three things that you could do, what would those three things be?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation So I think the most important piece is really this fundamental architecture question, right? Because as long as you have an architecture where you're going to have single points of failure, we're going have a world where we really have to trust some other entity with our data. And so I think the first and most important thing is making sure that we store our data in a way where users are actually in control, which just isn't the way today's web works. So I think the architecture is a critical piece.

I think a second and very important piece is also respect for individuals, for individuals' right to control their own data, for individual's right to privacy. And that's something that you you could get if you're willing to trust a third party to do that. But it's also something that you I think is even better to actually just bake into the technical stack instead of just saying, okay, well we'll force technology companies to respect people's civil liberties and privacy and we'll just trust that they're going to do that. Much better in my view to actually bake it into the technology.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And as leaders are considering ways to create solutions, that do just that, is there a question they should be asking themselves. What's a mindset or an awareness that people can be applying to make sure that they're doing that?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I think that it really is a question of are you comfortable with the way that your data is being stored, right? For many people maybe the answer is yes. But, you know, I think there are these moments where, you'll have like an AWS outage, for example, and then you're suddenly like, wait. "My toaster isn't working," You kind of realize how much of the world is really dependent on these centralized single points of failure. And I think that when you really start thinking about it, and actually think about what it means for you to have to just trust that the data is still gonna be there. I think when you ask yourself that question, you can start thinking a little bit more about where you want your data to be stored and how you want it to be stored.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Are there new approaches to collaboration that we'll need to be put in place in 10, 15, 20 years? What are your thoughts on this?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Well, I think that, you know, for us, we really are viewing this as the next generation of the web. Right? So we see Filecoin and IPFS as sort of a fundamental technology that enables a web where people are in control of their own data. So a lot of people will refer to this as sort of Web3 right, and with the idea that we're currently on Web2. And so there are all these sort of fundamental values of Web3 that really do bake in users being in control their own, data privacy and civil liberties protections and a lack of single points of failure that is really fundamental to what Web3 means. So I really see this as a fundamental technology, a foundational technology, for the next generation of the web.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And is there anything in particular that would really help it scale?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation In the sort of cryptocurrency space, the ability to actually add incentives is absolutely critical. Because we actually had built IPFS, the Interplanetary File System, which is the decentralized storage system, long before we built Filecoin. And so, you know, you can imagine you have this...decentralized file storage system where people can store files on other people's computers and other people hardware, and that's great. But if someone just stops storing it, the data is gone, you can't actually rely on it. So actually having built-in incentives where people who want to store your files actually put up collateral, and if they stop storing it they're going to lose that collateral. And where you have programmable money that actually is checking to make sure that things are actually stored the way you say they are, you're able to actually scale in a way that is just not possible if you don't have those monetary incentives, which is why cryptocurrency is such a fundamental part of building this technology.

The ability to actually add incentives is absolutely critical.

”Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader You helped found the Filecoin Foundation, was there any kind of turning point or moment where you said, you know, not only does this thing need to exist, but I'm the one who is gonna be best placed to sort of help shepherd it.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Well, I was very lucky to be an early lawyer in the cryptocurrency space, and I was very interested in cryptocurrency because of my background in civil liberties and being a civil liberties lawyer. And so I was lucky to get to work with the early team that was building Filecoin, which included open source developers around the world, also included a company called Protocol Labs, and got to be there initially outside general counsel and then general counsel and really got to help build, Filecoin from the ground up. And I was just absolutely delighted to get to be the person who founded the governance body for the network. And it's just been an amazing almost five years at this point and just incredible to get to work with this huge community of people all around the world. It's really been just an amazing five years.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader As I was doing research for our chat today, there was a conversation I heard that you had where, in early experience, there was Kindle document. It was a work of literature. I want to say it might have been like War and Peace or something like that. And every time, it was being transferred from the Kindle platform to the Nook platform. And each time the word Kindle had appeared, there had been maybe a rudimentary to find and replace, and it said, Nook. Can you tell me a little bit about that and sort of like what that meant to you about sort of thinking and rethinking about data and what we're storing. Yeah.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, absolutely. So back in, I believe this was 2013, people were reading on their Nook devices, which is sort of a competitor to Kindle, they're reading War and Peace. And they're noticing in the text that wherever the word Kindle would have appeared, so for example, "he kindled the fire," it was replaced with the word "Nook." So, you know, instead it would say, he Nooked the fire. And it is clear that what happened was someone had basically taken the Kindle version and done a find and replace intending to replace like the cover page where it said Kindle version with Nook version. But instead had accidentally replaced it throughout the entire book.

And at the time, it's 2013, that's funny, like it's sort of a funny thing, but actually It sort of makes you think -- this is sort of placing it in time, this is really before, you know, it was really before a lot of people were thinking about sort of what it meant for third parties to be storing your data. And to think that like your version of War and Peace could be so easily edited by a third party and you know in fact could be, if it's a digital version, could be taken away from you, right? Could be totally altered. Was actually, I think, quite chilling because it really is a moment of realizing and starting to think about, for me it was a moment to think, what does it mean that we really have to trust, in this case, Nook, but whatever the third party is, we really do have to trust them with our data. We're not in control of it ourselves. What does that mean in a digital world? And so that was an early experience for me of really starting to think about these issues.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader I want to talk a little bit about some other points in your background. There's a really interesting thing. You created a special nonprofit for teens. Tell me a little about this. This is when you were in college, correct?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, when I was in college, I was the executive director of a nonprofit called No Worries Now. And it's definitely a deep cut, I haven't talked about that in a while, but what we did was we held events and, you know, proms for teenagers with life-threatening illnesses.

But another thing that we did was, we did policy advocacy because, you now, I actually sort of in talking to a lot of these teenagers, I found out about this thing called umbilical cord blood banking. The idea is a lot of cancers are actually curable with a bone marrow transplant. So leukemia, lymphoma, sickle cell anemia, you can actually cure those with a bone marrow transplant. But the issue is you actually need to have a donor of bone marrow that matches you.

And it turns out that you can use bone marrow but the other thing you can for for this type of transplant is actually the blood that is left over in an umbilical cord after birth. And most of the time that cord blood is actually just thrown in the trash. It's just medical waste, right? So this is a life-saving unit of stem cells that we just throw away because we didn't have policy in place to bank it.

There were, at the time when I was working on this, there were some private banks, private cord blood banks, where people could pay a bunch of money to store their own cord blood. But that doesn't really make sense. The thing that really makes sense is to have a huge bank that is supported by the public where if someone has leukemia they can actually have a better chance of finding a match. Because meanwhile literally thousands and thousands of people every year are dying waiting to find a bone marrow match and we are literally throwing this in the garbage. It was wild to me.

And so it was really, I think, my first foray. Into this world of technology policy and seeing how being able to do advocacy around a particular policy, in this case about core blood banking, really has a huge impact on people's actual day-to-day lives. I think technology policy can be very abstract when you think about it. It's really hard to see with technology what, if you're doing policy work, what is the impact. But for me, I was already working directly with a bunch of teenagers with life-threatening illnesses. You know, some of whom died waiting to find a match, right? And so I could really see, you know and sort of had the faces of the people who were impacted by this policy work. And so that was, I was initially doing that policy work through No Worries Now. I also worked with the National Marrow Donor Program, doing policy work with them in DC for the National to basically lobby for the National Cord Blood Bank to be sort of funded. And then I also worked with a California assembly member, Anthony Portantino. On his bill to create the first public cord blood bank in California, which was successful.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader I think a lot of people wouldn't see the opportunity there. What did that teach you about these hidden opportunities to help?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I think the thing it really taught me is that there's the thing about the economist who says there's a hundred dollar bill on the ground, there possibly couldn't be because someone would have picked it up, that joke. It really taught that there are actually, in fact, a lot of hundred dollar bills on the ground. In other words, there are a lot opportunities out there, not even opportunities, but there are a lot of very obvious things. That are just not done, right? And particularly when you think about emerging technologies or any kind of technology, you know, often because we have this sort of new thing no one has really thought through kind of, and sat down and actually said, like, you know, in this case it was like, "hey, we should have a public cord blood banking system." It just seems blindingly obvious when you thing about it, like we're throwing this stuff in the trash. How about we cryopreserve it, and then we have a public bank so that people can actually get their matches from that public bank. Seems super obvious, but actually it takes a lot of work, it takes lot of effort and a lot of advocacy to get even those sort of blindingly obvious policies really implemented. And that is something I've definitely seen over and over again in my career working on policy and emerging technologies since then.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader You have another little interesting part of your background. You were the etiquette columnist at Berkeley at your college paper. Tell me about it.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I was. So many deep cuts here. Yes, I the etiquette columnist at Berkeley. Yeah, had a column, and it was all about sort of applying, you know, not this kind of stodgy type of, you know Cotillion etiquette, but rather applying kind of rules of etiquette to college life. Like, what does it mean to have sort of good etiquette at a frat party, right? Like what does that mean? And I think fundamentally what that comes down to is really about sort of Being considerate of other people and the very important element of people in other people in our sort of everyday lives, I think that's something that has been an ongoing theme for me because even just like fast forwarding to now as I'm leading the Filecoin Foundation, which is the governance body for the FileCoin network, sure we're working on this very sort of like high-tech kind of technology. But at the same time, what we're actually doing is working with thousands of people all around the world. Storage providers, developers, users, people, right? And it's all about coordinating people and being considerate of other people. And I think that that's something that is just a continuing theme for not just me, but really for everyone.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader I have to ask you, for instance, an etiquette at a frat party, what does that look like?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation What a great question. I would say, first of all, I hope I, for the most part, I am anti-link rot. But I will say, when it comes to my college etiquette columns, maybe I'm pro-link-rot on those.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader I couldn't find a single copy of it.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Glad to hear it, glad to hear. I'm sure there's a physical copy somewhere, but I'm pro-Linkrot in this one case. You know, I think the idea there was really, not to try to apply some sort of stodgy, Emily Post type of etiquette, but it was really about, for example, if you go to a party with your friend, right? Like, the etiquette around. Let's say one of them wants to leave early, but the other one wants to stay, right? Like, how do you navigate that? Really being considerate of others and what that looks like in a bunch of sticky situations that you find yourself in in college.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And in etiquette, which is at its heart, of course, is just codes of conduct. How do we treat each other? How does that inform your work in doing decentralized filing and protecting our most important information?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I think it's a really good point. I really think that fundamentally any technology in my decentralized web space is really about connecting humans. So when you have this Web3 space, in the decentralized universe, you really have technologies that are all about peer-to-peer interactions. They're all about being able to interact. Transact directly with each other instead of having to do it through this nameless, faceless set of a few corporations. I do think that fundamentally this is a technology that is really about people, which I think is a really important part of what the future of the web looks like. It's like, what is the web if you really think of it as the internet of people?

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader For your Stanford Law graduation, there's a really interesting thing where while everyone else is sort of vying to do the speech by themselves, you proposed a really interesting idea of the Wiki speech. What is the Wiki Speech?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, so in graduating from Stanford Law School, there was an election for a graduation speaker. And so I proposed and ran on the platform of, well, instead of having one person write the graduation speech and give the graduation speech, why don't we write it all together? Like why don't we do, why do we collaboratively write this speech? So I won the election and we did. It was at, there were 180 class members. Over 100 participated in the process, and what we did was we used an online wiki, so similar to Wikipedia, right, where you can actually use this online tool -- thousands of people, millions of people around the world edit Wikipedia, and you get these really polished and very highly researched and, you know, wonderful articles -- and similarly, my thinking there was, well, let's use that same technology, that same Wiki technology, to collaboratively write a speech.

And with Wikipedia, a lot of people say it's a good thing, it works in practice, because it would never work in theory. And it was sort of the same with the Wiki speech, which is I think in theory that sounds like a terrible idea, like having over 100 people write a graduation speech just sounds like a horrible idea. In fact, it totally worked. It was great. We had in-person editathons, much like Wikipedia editathons. We had a structured process that we enacted through wiki technology, and it all worked. And it was a great moment of collaboration, open sourcing. And, you know, it's something that was just really, it was a very Stanford way of doing things. So I'm really glad we did that. It was 10 years ago, but it was really a great way to kind of kick off my career.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And what's the special sauce to that, right? Because I would bet that a lot of people, if they said, hey, let's do a Wiki speech, we'll all chime in on this. It wouldn't go so smoothly. In your mind, what were the one or two magical things that really made it work, made that collaboration sing?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, it's all about process. It's really all about process and I think one thing that's really important is, it's funny because I'm comparing it now to what I do now, which is open source governance. It's actually a very similar set of problems which is like, okay, we want to create some change in the network. I'm just doing a metaphor here. But we want have some change of the network, we have thousands of participants. What is the process through which we get consensus from thousands of people on this particular set of code or this particular proposal. And similarly the special sauce with the Wiki speech was really like what is the process that you go through to actually be able to get to a speech.

And what we did at the time was we designed a process where basically we started with and overall throwing out ideas for kind of themes. And people threw out sort of like. Here are a bunch of stories I have within each of these themes. So like funny stories about professors, stories about our first week at Stanford, things that we are really proud of that we did. And we got this huge amount of content that people contributed. And then we had sort of a next stage where we kind of looked at it together and said, well, what are some themes that are standing out? And created a shape of the speech from there. And then kind of, from there slotted things in. So it isn't a free for all, similar to how open source governance is not a free-for-all. It's a process. But it's a a process that enables you to really collaborate and harness the wisdom of the crowd and really make it so that it's not something that's chaotic, but actually something that benefits from having all of these different eyes and different pencils on it. And it's, you know, I think as I said, it's a good thing that it worked in practice because it definitely doesn't work in theory.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader If I'm a leader listening to this, and I want to take something from this, is there a question they should ask themselves as they're developing a process to make sure that people's, for instance, voices are being heard as well as the project is moving forward? What would you ask them to consider to make that they are designing a process that reflects A. their values but also the goal and the group.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Well, let me tell you about one of my favorite things to do with my executive team or any other sort of team I'm working with, which is when we're sort of trying to, when we are at the beginning phases of something, we have some goal we're trying to achieve and we are developing strategy to get there. We like to do a thing that I call a bad idea brainstorming session.

And so what I'll do is I'll say, okay, well let's just take 10 minutes and we'll have a Google Doc or other collaborative tool. And everyone just write down five bad ideas. They have to be bad ideas and, you know, go. And so we just give people time and people sort of add bad ideas to this collaborative document. And it's really incredible because it's very freeing for people to be able to express their ideas in a way that is free from judgment because as you can imagine you often actually get kernels of good ideas in those bad ideas. And so you end up getting these much more creative kind of things by really taking away the judgment and making it okay to have bad ideas and it also introduces an element of sort of like. Playfulness and not taking ourselves too seriously because people will put also genuinely bad ideas that are usually quite funny So it's it's a really great way of like changing the vibe and and a really Great moment in a in a process where you can really Gain ideas from people that they might otherwise not be willing to share and really get kernels that are quite creative and also Have a really have a great way, of really Involving everyone and getting everyone in a much more creative and playful headspace

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And is a question someone can ask themselves if I'm kind of not used to this sort of brainstorming, sort of open source approach to writing. Is it just, do people have a voice in this? Is that, would that be simple enough?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I think that's right. I think the idea with any kind of open source, whether it's open source technology, an open source speech, or just an executive team, is really making sure that you're able to hear from everyone and really believing in the wisdom of the crowd. That doesn't mean everyone is right, but it does mean that everyone is heard.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader You practice a thing called work-life integration. What is that?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I've only recently started talking about this. I've said it sort of privately to people for a long time, but I don't think work-life integration is for everyone. I think I totally respect people who have sort of standard work- life balance boundaries. That makes sense for a lot of people.

For me, and the way I work, I work a little bit differently, which is, I'm really coming from this very mission-driven space where I care a lot about civil liberties. I care about using the technology stack to really embed civil liberties, and the people who I work with are the people that care about the thing that I care about. And so the people I'm hanging out with are also the people who are interested in the thing that I'm working on,

And so I think there's an element of -- and I think you see this a lot in like activist communities -- there's an element of we as a you know being able to hang out with the people who you're working with and genuinely like them and genuinely have that be a big part of your sort of community and also being able to work with the people in your in your social world. You know, my partner for example is is very much adjacent you know we don't work directly together but you know one of our early experiences was we both submitted amicus briefs in the same Supreme Court case. You know that kind of thing. We're very very very much in the same universe and I've just been so lucky to be able to have a community of people who have sort of through life been you know colleagues at one time then friends then colleagues again then friends. And being able to really integrate that is it really allowed me to integrate my work in life where I'm not Clocking out like there isn't a moment where I am not you know even when I'm socializing. I'm working and when I am you know, working and also socializing.

And I think there's also an element of work-life integration which is, I think for many people, there's a concept of this is my work time and this is social time. And that's great, that works for a lot of people. It doesn't work super well for me. I do think the idea that, for example, of a nine to five, that a human can come in to a job at 9 a.m. And focus until 5 p.m. with one lunch break and that that's when they're going to do their best work is also just fundamentally flawed. And if you look at the way that, like, for example, like... Famously, Mozart had a schedule where he would work from 7 to lunchtime and then not work at all from lunchtime until 5 or 6 p.m. And then work from 5 or 5 p. M. Until bedtime. I think the idea of being able to integrate your work and your life such that you don't have these set schedules, but you can work when you're inspired to work or when you need to work, or when it's the most convenient way to work and not be so set on this idea of. I need to switch off my device and be done with work at this particular time, or I need to be at work and can't possibly do anything personal in this particular period either. So that's my kind of theory of work-life integration, which works for me. I fully understand would not work for everyone, but it's something that has really allowed me to thrive.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And are there tells that it's working well, right? A lot of people might get a little bit nervous as you're explaining this, and it's because maybe it's draining energy from them to have everything all in one bucket. In your mind, is it that it is energizing you? What is it, a tell, that this system is working right so people who are maybe going to explore it can kind of think about that?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I think I can totally imagine a world in which this does not sort of organically work for someone? That is totally fine. I think we all work in very different ways. And so I do think there's an important part of like does something feel or come kind of naturally or organically. But I think the idea really is not to force yourself to integrate your work and your life but really to just free yourself from this idea of I need to balance work and life as these two totally different things that work has nothing to do with and life has nothing to do with work. I have to switch off my phone at this particular moment in time and just free yourself from that idea and see whether freeing yourself from that leads to you organically feeling like you're in a good place and able to integrate things in a way that feels seamless.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader How do you think you have changed as a leader in your career? Is there something that you do now that just would not have occurred to you when you first started working?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Yeah, I think I change constantly, actually. I'm a big growth mindset person. I'm big proponent of a lot of feedback and a lot radical candor. And so I really see myself changing often week to week. I'm constantly iterating. I'm very iterative, similar to how you would iterate on technology or a product. I'm very iterative, sort of in my leadership style. And so, you know, I'm constantly coming up with, you know, well, let's try this out and see if it works. So let's try this. Or, you know, or I gave the example of bad idea brainstorming sessions. Right. That was something we iterated on and it turned out to really work. But, you know, other iterations include things like, you know, making sure that I'm not on even just something like being on back-to-back Zoom meetings all day. Right. And having no breaks. I had this moment recently where I saw this picture. They did these brain scans of what people's brains look like when they do back-to-back Zoom meetings with no breaks in between, and then they show the brain scans of people who do take breaks, and it was just like, I just had this moment of, oh, my God, that is wild, that it's so stressful. And so we actually implemented that across our entire organization. All meetings are now 25 minutes instead of 30 minutes, and that's organization-wide. And so that's an example of an iteration that has really helped me personally, and I think a lot of the folks at our organization, but we're constantly iterating, and that, to me, that's really important to me, a growth mindset and iteration is really important to me as a leader.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Other ways you guys collaborate, where you run meetings or the way you share information, that you're not really like, gosh, that's really worked for us, but that may be unique.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I mean, everything we do is in sort of Google Docs and collaboration. We constantly do, I mean sort of taking from the Wiki universe, we often do edit-a-thons where we just go on silent, we're all there together, but we just on silent and work and collaborate in a document together. And that's an example of something that we've really taken from our sort of like open source roots. And, you know, we... You know, we are constantly sort of looking for better ways to collaborate. We're fully remote. So it's also, you know, it really is sort of working on hard mode. And not only that, but we're not an organization, we're not Intel where it can be like, okay, you work on this and you work on this, and you're working on this. We're really coordinating this large, broader ecosystem of people all around the world. So there is a lot of, there is not, you know, it is not one approach, like there's a lot of, um, there's lot of iterating, there a lot sort of making it up as we go along and just trying to make sure that we can collaborate with people in the way that makes the most sense for them.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader: Is there a piece of advice that you've always been grateful for?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation So I probably once a day say, "Low expectations are the key to happiness." That is like, I truly believe that. That is one of my sort of like core principles. And it's something that I come back to every single day.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader: How does it help you?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation: Well, I think it's, I just think it critical to set expectations, you know, in the right place. Thank you. Another thing I say often is "Done is better than perfect." because I think it's really helpful, especially for executives or people who are really perfectionists. It's really freeing to be able to say, to lower your expectations for yourself in some ways and to say look, I'm going to get this done rather than get it perfect and again to not have that pressure on yourself. So for me those two phrases are really on repeat.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Is there a book that you recommend?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation So my executive coach wrote a book called From Startup to Grown Up, and it's fantastic. It's just a great book. And it really helped me sort of think through what it means to be a founder and to be leader.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader How have you changed? If somebody else read that, how would they change?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation You know, I think that particular book is extremely tactical. It's just, I mean, for example, one of the things that stood out to me in the book that just jumps to mind is a passage about how you have to say things so many times to get them through to people that you'll know that you've succeeded when it becomes like a joke. Like when you've said something so many times that people are kinda like, ha ha ha, cause they know you're about to say the thing and it's like a jokes cause you always say the thing.

Like, for example, I always say... We have a thing called the directly responsible individual, the DRI. And I always say, who's the D.R.I.? Because if you have an action item and you don't have a directly responsible individual, it's not going to get done. And so it has literally become a joke that people will say, who's a D. R.I. Because it's this thing. But it really has helped to bake in, like every task needs a DRI. And we have a set of leadership principles, the Filecoin Foundation leadership principles that are based on Amazon's leadership principles. And one of our leadership principles is everything needs a deadline and everything needs DRI

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader We are nearly done. Before I let you go, Marta, we have a little thing, rapid response. It's a little fun back and forth. Where I'll say something and then you'll fill in the blanks and you respond to it. So the first one, what's the first thing you do every morning?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I check my sleep data.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader How's it going so far?

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Well, it's great, yeah, I have an eight sleep system and it's like a report card. It's like, how did I do? Do I need to go back to sleep? Do I some more deep sleep?

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Go to Karaoke song.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I like Stacey's mom because you can't take yourself too seriously when you're singing it. And I think that's very important.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Biggest work pet peeve:

I hate it when people use acronyms that other people, they're not 100% sure everyone who's reading it will know. I hate that.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader The best thing you've stopped doing.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Well, I've stopped doing back-to-back Zoom meetings and have always now have a five-minute break at minimum between Zoom meetings, and that is huge.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader: Habit you can't work without.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I exercise every day and I do that before I work 365 days a year for over 10 years and it is non-negotiable and it is I would say more of an addiction than a habit but absolutely critical for my work life.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader File you hope never disappears.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation Oh, gosh. You know, I'm Ukrainian. And so I would say the work that we've done with the evidence of war crimes in Ukraine is very, very near and dear to my heart. And I am so glad that we are preserving that on the network.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And the biggest challenge that you see for the rest of 2025

Marta Belcher, Filecoin Foundation I think in 2025, the biggest challenge is really, is law and policy going to get in the way of innovation for AI?

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader Well, thank you very much, Marta. I really appreciate you coming here and talking with us today.

Marta Belcher, Filecoin FoundationThanks so much for having me. This has been great.

Linda Lacina, Meet The Leader And for all of our viewers and our listeners, check out more video podcasts on our channel for the World Economic Forum on YouTube. And for more transcripts, go to wef.ch/podcasts

トピック:

グローバルリスクその他のエピソード:

もっと知る グローバルリスクすべて見る

Belisario Contreras, Cristina Camacho, Thelma Quaye, Vilas Dhar and Iyad Rahwan

2025年10月8日