Anxious Generation: how to tackle a mental health pandemic

ポッドキャスト・トランスクリプト

Jonathan Haidt, author, The Anxious Generation: Imagine if when we went to school, they said, you can bring in your television, set, your VCR, your guitar, your paint by numbers, Play-Doh, whatever you want. Bring it in, play with it during class. I mean, that's completely insane. And of course, you wouldn't be able to learn anything. And that's what's happened since 2012.

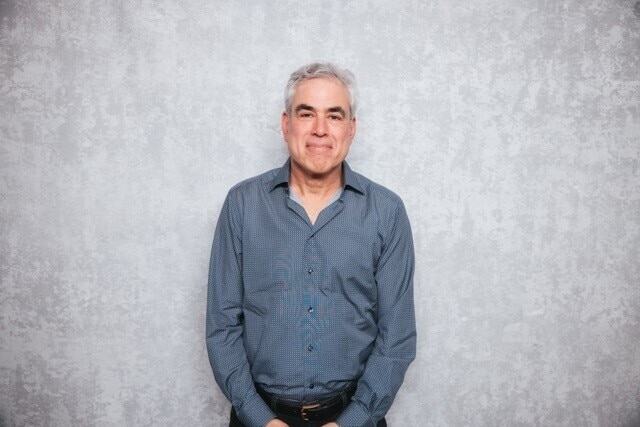

Robin Pomeroy, host, Radio Davos: Welcome to Radio Davos. I'm delighted to have as a guest Jonathan Haidt, who is the bestselling author of The Anxious Generation.

Jonathan Haidt: For the last ten years, it's been mostly kids just staring down. And this is a big reason why they are so lonely.

Smartphones with a front facing camera, high speed internet and super addictive, super viral social media on the phone, which wasn't possible in 2010.

And so it's that period in which there's a rewiring of this flow of development. And the kids are coming out different and I would say diminished.

This is a collective action problem. But if we work together, we're making amazing progress

Robin Pomeroy: Hi Jonathan, How are you?

Jonathan Haidt: Fine, thanks, Robin.

Robin Pomeroy: I've been a fan since I discovered The Happiness Hypothesis. That was your first book, right?

Jonathan Haidt: That's right. It grew out of my teaching Psych 101 at the University of Virginia and finding that ancient ideas often illuminated modern psychology. And I just collected a bunch of quotations from the ancients. And guess what? It turns out they were totally wrong about chemistry, physics and things like that. But totally write about consciousness and social life.

Robin Pomeroy: I love the book, and if you describe it as you've taken ancient wisdom or whatever, it sounds a bit, with all due respect to Hallmark, like a Hallmark card. But what you've done in that book what you've done in The Anxious Generation is have hypotheses and test them against evidence. Let's talk about The Anxious Generation. This has made a real stir over the last year, I think, around the world. Tell us in a nutshell what that book is.

Jonathan Haidt: So The Anxious Generation is an attempt to explain why it is that the students entering my college classes and everyone's college classes in 2014-2015 were so different from the millennials.

We thought they were millennials at the time, but they were much more anxious. They saw threats everywhere. They wanted trigger warnings.

And so I've been working on that problem since 2014, 2015. What happened? Because it wasn't just college students. It turns out it was everyone in America born in 1996 and later. And then it turned out it was the exact same in Canada and the UK and Australia. And in more recent years, it's true in Europe too. We found that it's true in Europe too.

And so the book is an attempt to explain that. And it boils down to a very simple formula, which is that we have overprotected our children in the real world. That is, we blocked them from free play, independence and risk taking, and we've under protected them online that, that is we said, you can't go outside, it's too dangerous. But, oh, sit in your room and talk to sexual predators around the world, like, you know, whatever, it's online, you're safe.

So it's those two mistakes that the book is trying to call attention to and then give parents and teachers and legislators tools and ideas and simple norms to roll back this phone-based childhood and return to a play-based childhood.

Robin Pomeroy: You call it the great rewiring. What is that?

Jonathan Haidt: I think developmentally, I think about a child growing into a into an adult within a cultural context. I think about like a river, like a flow, you know, or like, you know, like electrical current or something moving along.

And then the technology changed. Of course, it's changing continuously, but there's a period 2010 to 2015 when it changes really radically. We'll come back to that in a moment. And it's that period, 2010 to 2015, that's when you find the elbows in all the graphs, that is levels of mental illness, especially anxiety, depression, were pretty stable from the late 90s through 2010, 2011, no sign of of a trend. And then all of a sudden it's as though someone turns on a light switch and the levels of anxiety and depression skyrocket, especially in girls.

And so I'm trying to figure out what changed. And the answer, at least what I say in the book, is that in 2010, teens all had flip phones. The iPhone comes out in 2007, but teens don't really have it in 2010. They have a flip phone. They use it to call and text their friends. And so they are still going to, they're still spending time with their friends. They're still looking at people in the eye. But by 2015, they've traded in their flip phones for smartphones with a front facing camera, high speed internet and super addictive, super viral social media on the phone, which wasn't possible in 2010.

And so it's that period in which there's a rewiring of this flow of development. And it now is not the ancient, you know, millions of years old, path of childhood to adulthood. It's now on screens, online, and the kids are coming out different and I would say diminished.

Robin Pomeroy: And is it kind of a two-way thing you say that having this addictive thing in your hand all the time, it blocks opportunity for what used to be social interaction in the real world. And also there's the potential damage from the content itself. So it's kind of a double hit from that. And I think what one thing is interesting, you talk about phone bans, I know you're very active campaigning to get smart phones banned in schools and a lot of schools ban them in the class but then not at break time or recess.

Jonathan Haidt: What I found is that here in Europe, people just love the word ban. Every wants to talk this as a phone ban. Whereas, you know, in America, we don't like bans unless they're absolutely necessary. And so I call this a phone free school. It's a positive. It's a virtue.

So phone free schools is what we need to have.

I mean, think about it this way. When you know, I don't you know, you and I are I don't I can't tell exactly how old you are, but we're from roughly the same time, I imagine, the 1960s. And imagine if when we went to school, they said, you can bring in your television, set, your VCR, your guitar, your paint by numbers, Play-Doh, whatever you want. Bring it in, play with it during class. I mean, that's completely insane. And of course, you wouldn't be able to learn anything. And that's what's happened since 2012.

Test scores in the U.S. and around the world, as we know from the PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] data. Well, in the US, they were rising from the 70s through 2012, and then they began to fall. And this wasn't because of Covid. They fall after 2012. Same thing with the PISA data.

So as soon as we stuffed kids full of screens and not just their phones, but also all the educational technology, they're so distracted, they can't learn.

So in response, some schools, and France did this first, they said, we're going to ban phones - in the classroom. Which means that every teacher now has to be the phone police because the kids have access to their phones in their pockets or in their backpack. And what that means is that the kids are desperate to get to their phones, beginning 5 or 10 minutes before class ends are thinking about it. Many of them are heavily addicted. And then in between classes, they're all on their phones. And then in the lunchroom, they're on their phones.

And when schools go phone free, and this is happening around the world, when schools go phone free. And they say, no, it's for the school that you come into school. You need the phone to get to school perhaps. You put it in a special phone locker, you put it in a Yondr pouch, you put it just in an envelope at the front of your homeroom class. When schools do this, what they all say is that we hear laughter in the hallways again. They say the lunchroom is loud again.

Because for the last ten years, it's been mostly kids just staring down. And this is a big reason why they are so lonely. The more you connect to generation by digital technology, the lonelier they are.

Robin Pomeroy: Generations past would say, oh, kids watch too much television, it's rotting their brains. And then maybe a generation later it's they worried too much about that. Could this just be that, you know, it's rotting their brains. You're an old fuddy duddy, Jonathan, is what I'm saying.

Jonathan Haidt: In theory, it could. And that is the main argument against me, that this is just another moral panic. But let's look a little closer. It is up to me to show that this time is different. I think I can do that.

In previous moral panics, you didn't have a sudden, instantaneous international collapse in anything. But in this you do. And there's no other way to explain why mental health goes haywire, not just in the U.S., but in Australia, New Zealand, Scandinavia, many, many countries.

And television is really, really different in two ways. First, the dose makes the poison. So there were kids who watched ten hours a day and I bet they were messed up. But you and I probably watched one to three hours a day, typically. And then you'd go outside. Even if you're with a friend, you watch TV for a while and then you go outside and do something.

We couldn't watch TV ten hours a day. But when you go from a flip phone to a smart phone, you can. And half of all kids in the United States, half of all teens, say they are online almost all the time or almost constantly. The phone is always in their hand. You can't do that with TV.

And so 2 or 3 hours a day of television doesn't seem to be terribly damaging. 7 to 12 hours a day of scrolling and comparing and not doing anything else is damaging.

So this time is very, very different.

Robin Pomeroy: I read a one star review of the book in Nature something along the lines of, Yes, it's all good supposition, but you don't test it agianst evidence, which I was quite surprised by. How do you respond to that?

Jonathan Haidt: Well that that essay in Nature by Candice Odgers who is who's a leading researcher in this area, she makes a number of assertions that I think are not true.

She says that I only have correlational evidence, but I don't. I have many kinds of evidence of causality.

So the first is that there are about 20-25 experiments where you have people get off social media for a couple of weeks and you look at what happens to the mental health. And you use random assignment. I mean, this is exactly what we mean by experimental evidence of causality. And when we look at those studies, what we find is that the ones that get kids off, usually college students, they get people off for a day, you think that's going to help them? No. If you're addicted to something, the first day or two is really hard. The first 4 to 7 days is really hard. But almost all the experiments that go for two weeks or longer, or even a week or longer. They all show benefits.

So, like, right there, like that is exactly the sort of thing that she was saying I don't have, but we have it.

Robin Pomeroy: You're in Davos. A lot of those big companies are here. Are you meeting them and what kind of conversations are you having?

Jonathan Haidt: I don't have time to talk with them here. And it's just I know the the oversight board is here. I might stop by that booth or that that that place on the promenade. I've spoken with Mark Zuckerberg on two occasions. I've spoken with the head of Snapchat on occasion. No contact with TikTok. In general, they're saying nothing about me. But, you know, they have a giant PR department and that PR department is doing its job and they're trying to control the narrative and spread the idea that, you know, it's just correlational evidence. Haidt doesn't have evidence. So as far as I can tell, they're not doing anything directly, publicly. But of course, they're trying to control the narrative. That is their job.

Robin Pomeroy: There's a chapter in the book where you move into spirituality, and this is very interesting from someone who's read The Happiness Hypothesis because a lot of that you test the ancient wisdom. A lot of that ancient wisdom is religious as well. Judaism or Christianity. And I often wondered what your own religion is, because in the book you talk about, I think you say you're an atheist, but you have a huge respect for the benefits of some religion. Can you tell us something about that? And also how then it could relate to this Anxious Generation?

Jonathan Haidt: Yes. Now, I'm so glad you asked about that, because that's my favorite chapter in the book, Chapter eight.

So I wrote this whole book about the devastation of young people. What this new transition is doing to young people. And then when I got near the end of the book, I realized, wait a second, like, I haven't said anything about adults.

And we all feel it. We all feel it's just too much and it's constant and it's a deluge. And what is this doing to us? And because I wrote this book, The Happiness Hypothesis, looking at ancient wisdom, I realized, whoa, almost every great truth that we get from the ancients about how to live your life, to have a better life, to be connected to God, to become a better person, almost every piece of advice we get, the online life, the social media life, the phone based life, tells you to do the opposite.

So, you know, the ancients tell us things like, judge not lest ye be judged. The general theme is, in so many religions, beautiful quotes in ancient Judaism, about the dangers of anger. Be slow to anger, be quick to forgive. This is ancient wisdom. What is life on Twitter? You better judge now baby because if you don't condemn them now, someone's going to condemn you for not condemning.

And give people the benefit of the doubt. Look at the context. Social media says there's no context. It doesn't matter. We're all just going to go crazy over this thing taken out of context.

And the ancients tell us, try to calm the buzzing cacophony in your mind. Sit quietly and you'll get an inner harmony between your mind and your spirit and the world.

But my students at NYU can never do this because they have to always be consuming content. Now they learn in my class, they learn to stop doing that, to take the earphones out, walk through beautiful parks.

So anyway, I realized, wow, this, it just matches on so beautifully, that the phone based life is the opposite of ancient wisdom and of human flourishing. So I wrote that up in a chapter.

And then to get back to part of your question, so I'm Jewish, but like many American Jews, raised in a very secular way, went to synagogue on the high holy days, I had a bar mitzvah and otherwise didn't do much. I was hostile to religion for a while because I was like a science kid and I was the sort of kid who would have become a new atheist like who thinks that religion is terrible, evil, get rid of it. But because I studied moral psychology and I wrote my second book was called The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. And in that book, I delved very deeply into the origins of religion, the evolutionary origins. There's no doubt about this. Humans evolved to be religious. We evolved to have sacredness, to form bonds, to circle around sacred objects. This unifies us as a community. Émile Durkheim got it all right.

And so once you see that now, suddenly you realize, whoa, the religious people actually have it right in terms of how to live. Now, that wasn't so clear 20 years ago, but they've been happier than secular people for a long time. After 2012, it's the secular kids who become super depressed and anxious. The religious kids only a little bit because they are grounded in a community and a moral order. And the secular kids were not. And they got washed out to sea by a million short videos and memes.

Robin Pomeroy: Because people who are anti-religion would say this is a way of controlling the masses, telling you what to do, from on high. You know, opium of the masses. You don't think that?

Jonathan Haidt: No, I mean, sure, that's a hostile thing that one might say. And there have been times when religion was more organized and controlling. And it might be also, you know, I come from the United States where there never was a state religion. The religions have to compete. There's an interesting theory. Why are Americans so much more religious? In part because we have a free market in religions. Our churches, they all have to compete. And so they have to attract people. They have to be innovative and they have to be fun. Whereas in Europe, you know, you have these state religions that are stodgy and boring and old.

So I have developed a great deal of respect for religion and the social functions of religion. Again, not all religions. Some religions lead to more violence, some lead to more more peace and calm.

But I myself, after I listened to a podcast by Ezra Klein with a woman who wrote a book about Shabbat, about the Sabbath, the Jewish Sabbath. And so recently I've decided to try to start honoring that myself. Even though I'm an atheist. Just one day a week when I don't try to do a million things to advance my projects. But I focus on people and books and regeneration. I can like clean up my closet. I can do things. But rather than the constant striving 24/7 seven, just one day a week.

I make a commitment to it here publicly. I just started a couple of weeks ago. So let's let's see if I can keep it up.

Robin Pomeroy: Because in the book you've mentioned, do you call it a digital sabbath? You suggest this is a way. Because I want to come, in this interview, to what do we all do now. And this is advice, I suppose, to adults. Maybe consider having a day off from your phone?

Jonathan Haidt: Absolutely. So I think it starts by realizing that for most of us, your attention has been drained away. And if you don't have your attention, then you're not going to amount to much in life. You're not going to get much done.

And so it starts with that realization. And what do you do? Well, you have to change your daily habits. Turn off most notifications. My students, almost all of them, the first thing they do when they open their eyes is check their messages. The last thing they do before they close their eyes at night is check their messages and DMs and scroll through things.

So you've got to change, change your habits, regain your attention.

But the other big piece of it is, is getting back into real life relationships. There's a fabulous essay in The Atlantic out right now by Derek Thompson called I think The Lonely Century [The Antisocial Century], about how the technology has allowed us all to bypass everyone else. We can do whatever we want instantly with no human contact. And this is a complete disaster for, not just society, but for individual happiness.

And so finding ways to embed yourself in more real communities, if you're at all religious, I would suggest being more active in a church or synagogue or religious organization. If not, do a digital sabbath. Try to identify a period of 24 hours when you don't or you don't or you completely minimize your use of technology. But it really helps if you have a community, if you have at least a few friends to do it with.

And then you'll find yourself just much more open to actually having a long conversation or a long meal and not rushing off to check something.

Robin Pomeroy: So that's advice for the grown ups. So what advice to the kids or to the parents of kids? I think you're saying until the age of 16, is that right, you shouldn't have mobile internet?

Jonathan Haidt: So in the book, I recommend four norms because we're all trapped in a collective action problem. Each parent trying to do this on their own faces is the universal refrain. Mom, I'm the only one who doesn't have Snapchat, a smartphone, whatever.

So when you try to do it alone, it's very hard. What we need is clear norms that we can all follow, and they're not that hard if we do them together. Here they are.

No smartphone before age 14, or high school in United States, but age 14.

No social media until age 16. Social media is wildly inappropriate for children - talking with strangers, getting addicted.

The third norm is phone free schools. And that's happening around the world at lightning speed. If you're listening to this podcast and your kids go to school where you can text them during the day, your kids are not getting as nearly as good an education as they could if they could be fully present in school.

And the fourth norm is far more free play and independence in the real world. If we're going to take them off of the screens for 10 to 15 hours a day, we've got to give them back fun, excitement, adventure, play, real life.

So if you go to anxiousgeneration.com, the book's website, we have all kinds of tips and links and resources for parents, for teachers, for legislators. Because this is a collective action problem. But if we work together, we're making amazing progress this year. The book came out in March [2024] and already, you know, countries are raising the age, countries are changing laws. About a dozen U.S. states have now moved to ban smartphones.

Robin Pomeroy: I was going to ask about that, so the book came out in March 2024, I think Brazil is the latest country to ban mobile phones.

Jonathan Haidt: That's right. Let's not say ban, I say go phone free. Brazil is going to go phone free. Indonesia just last week, Indonesia said they're going to follow Australia's lead. They're going to raise the age. They haven't said what age, but I'm hoping at 16.

Robin Pomeroy: Is that the right approach? Is that what you'd like to see?

Jonathan Haidt: Yes. We can't do this on our own. The companies are too smart and they've understood the collective action, social pressures. But we can use those collective action dynamics to break out if we do it together at the same time.

Robin Pomeroy: My daughter's 11. She keeps asking me why am I getting my phone? And as I'm reading this book in preparation for Davos, I'm saying, this guy's telling me, you're not getting a phone any time soon.

Jonathan Haidt: No, hold on. Hold on. Don't confuse phones with smart phones. A smart phone, you can make a call on it, But it's not it's not a phone. It's a multi entertainment, you know, portal to talk to everyone in the world, including all the men who want to talk to your daughter. So, you know, at what age should you be talking to, you know, perverts and sex abusers? And I think we should at least wait until you're 16 to do that.

Robin Pomeroy: Something to look forward to, isn't it!

Jonathan Haidt: So my point is my point is you can give your daughter a flip phone or a phone watch that you can text with or she can text with you. She can check with your friends. She does need to be in contact with them in order to do things. And that's what I want to encourage. If all kids had a flip phone, they wouldn't be on it all day long. They'd be saying, Meet you at three at the pizza parlor, and then they would meet and that would be great.

Robin Pomeroy: She has one of those watches. I was so relieved when I got to that part in your book. I was thinking, oh no, I've already done it...

Jonathan Haidt: No, you're doing well.

Robin Pomeroy: And one other advice for kids. We have to wrap up in a moment. Internet's great, isn't it? There's so much great stuff on there. How should we be supervising children at this very impressionable age, where they could be rewired, through puberty, where they can get great stuff from the Internet without it making them part of the anxious generation?

Jonathan Haidt: That's right. So it's in part the dose makes the poison. And so, you know, if a five year old, if you show him how to Google something, that's okay. What I would suggest especially with young kids, get a desktop computer, put it in the kitchen or a common room. The kids can use it sometimes.

But I wish I had followed the rule no screens in the bedroom ever. No screens of any kind of bedroom ever. And then when they get to age, you know, ten, 12, 13 middle school, then you can say, okay, two hours a day of homework, you can bring in a laptop for homework, but it doesn't stay in there. I wish I had done that because the phone is the most addictive, and social media is the worst part. But you can do most of that on your laptop, too.

And so we've got to get our kids to stop being so stimulated because when kids are stimulated constantly for, let's say, half the day, the other half of the day is painfully boring. The dopamine circuits are like, Wait, where's our stimulation? So we've got to basically reduce the amount of time kids are spending on the internet and on screens by 70%, 90% when they're young.

Robin Pomeroy: What should leaders be prioritizing in 2025?

Jonathan Haidt: The biggest thing they can do for teen mental health is follow Australia's lead, raise the age to 16 for social media and require the companies to figure it out. They can do anything. There are already lots of ways to authenticate ages without having to show a driver's license or government ID.

If we put raising the age with enforcement here, and we put all the tweaks and algorithm stuff and, you know, over here, just raise the age, that's so much better than everything else combined.

Robin Pomeroy: Is there a book, apart from your own, that we should all be reading in 2025?

Jonathan Haidt: Well, I would recommend what really helped me and my students is a book by Cal Newport called Deep Work, and it really is about how to regain control of your attention, because without that, there's no point in trying anything else.

Robin Pomeroy: Jonathan Haidt, thanks so much for joining us on Radio Davos.

Jonathan Haidt: My pleasure.

Scroll down for full podcast transcript - click the ‘Show more’ arrow

In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt says there is clear evidence that giving children smart phones with addictive social media has caused a mental health pandemic.

The NYU-Stern social psychologist, who also wrote The Happiness Hypothesis, spoke to us at the Annual Meeting 2025 in Davos.

その他のエピソード:

「フォーラム・ストーリー」ニュースレター ウィークリー

世界の課題を読み解くインサイトと分析を、毎週配信。