The trouble with trying to ban 'killer robots'

In safe hands? Weapons are increasingly automated, raising new ethical questions Image: REUTERS/Mike Blake

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

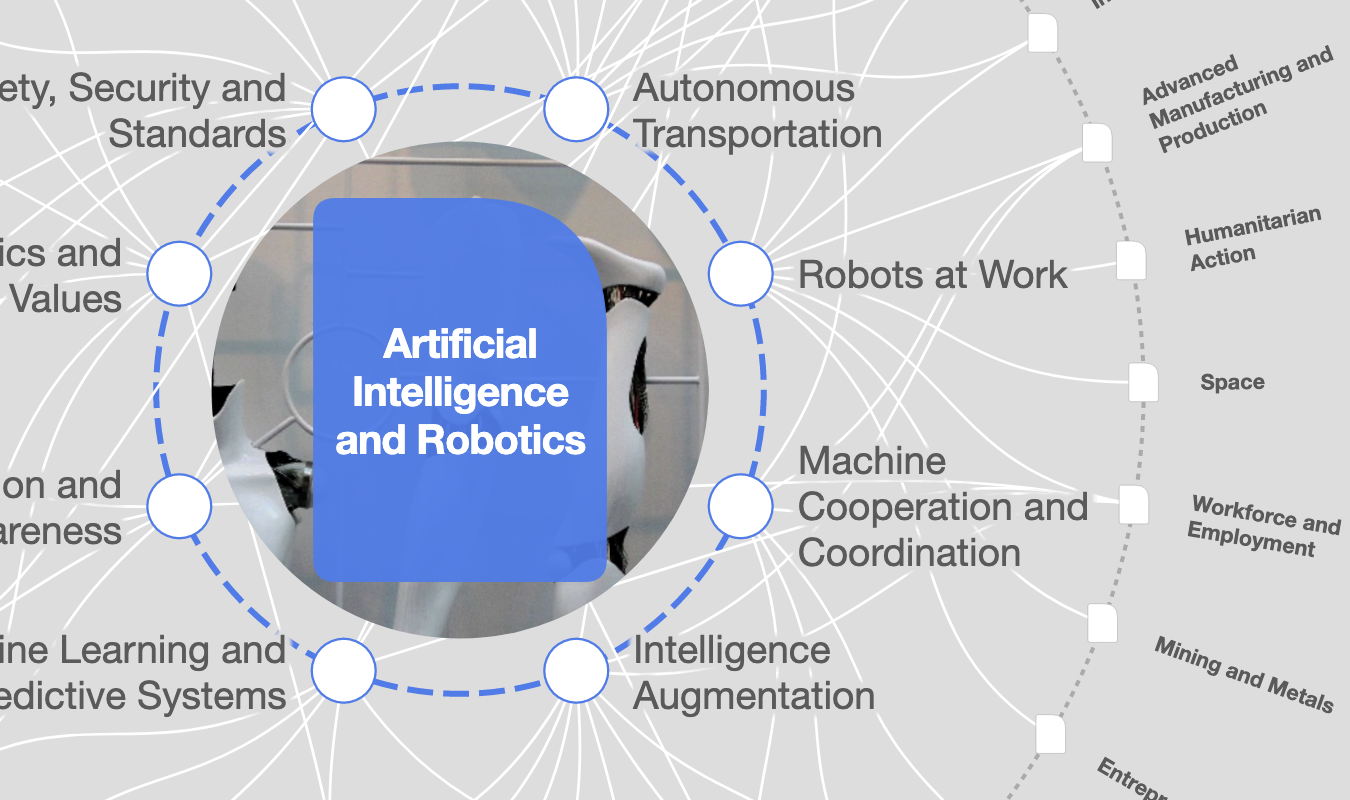

Artificial Intelligence

Last month more than 100 robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) company CEOs signed an open letter to the UN warning of the dangers of autonomous weapons.

For the past three years, countries have gathered at the UN in Geneva under the auspices of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons to discuss the role of automation and human decision-making in future weapons. The central question for nations is whether the decision to kill in war should be delegated to machines.

As in many other fields, weapons involve increasing amounts of automation and autonomy. More than 30 nations have or are developing armed drones, but these are largely controlled remotely. Some drones have the ability to take off and land autonomously or fly pre-programmed routes, but any engagement of their weapons is entirely controlled by people. Advances in AI and object recognition raise the spectre of future weapons that could search for, identify and decide to engage targets on their own.

Autonomous weapons that could hunt their own targets would be the next step in a decades-long trend toward greater automation in weapon systems. Since World War II, nations have employed “fire-and-forget” homing munitions such as torpedoes and missiles that cannot be recalled once launched. Homing munitions have on-board seekers to sense enemy targets and can manoeuvre to correct for aiming errors, and zero in on moving targets.

Unlike autonomous weapons, however, they do not decide which targets to engage on their own. The human decides to destroy the target and the homing munition merely carries out the action. Some weapons also use automation to aid humans in making the decision of whether or not to fire. Today, radars use automation to help classify objects, but humans still make the decision to fire – most of the time.

Sometimes, the speed needed to counter enemy threats necessitates taking the human “out of the loop” and letting machines decide when to fire on their own. For example, humans cannot possibly react fast enough to defend ground vehicles from anti-tank rockets and missiles, so countries have adopted active protection systems to automatically sense and defeat these threats. More than 30 nations currently employ human-supervised, autonomous weapons to defend ships, vehicles, and land bases from attack. This means humans supervise intervene if something goes awry, but once the weapon is activated, it can search for, decide, and engage targets on its own.

Advances in robotics and autonomy raise the prospect of future offensive weapons that could hunt for and engage targets on their own. A number of major military powers are developing stealth combat drones to penetrate enemy airspaces. They will need the ability to operate autonomously deep inside enemy lines with limited or no communications links with human controllers. Countries might decide to limit these drones to only attacking fixed targets that have been pre-authorized by humans, much like cruise missiles today. But countries might decide to allow drones to search for and destroy new targets on their own.

What would the consequences be of delegating the authority to weapons to offensively search for, decide on, and engage targets without human supervision? We don’t know. It’s possible that they would work fine. It’s also possible that they would malfunction and destroy the wrong targets. With no human supervising their operation, they might even continue attacking the wrong targets until they ran out of ammunition. In the worst cases, whole fleets of autonomous weapons might be manipulated, spoofed or hacked by adversaries into attacking the wrong targets and perhaps even friendly forces.

A growing number of voices are raising the alarm about the potential consequences of autonomous weapons. While no country has stated that they intend to develop autonomous weapons, few have renounced them. Most major military powers are leaving the door open to their development, even if they say they have no plans to do so today.

In response to this, more than 60 non-governmental organizations have called for an international treaty banning autonomous weapons before they are developed. Two years ago, more than 3,000 robotics and AI researchers signed an open letter similarly calling for a ban, albeit with a slightly more nuanced position. Rather than a blanket prohibition, they proposed to only ban “offensive autonomous weapons beyond meaningful human control” (terms which were not defined). Interestingly, authors of the most recent letter did not call for a ban, although they did demand some kind of action to “protect us from all these dangers.”

One of biggest challenges in grappling with autonomous weapons is defining terminology. The concept of an autonomous weapon seems simple enough. Does the human decide whom to kill or does the machine make its own decision? In practice, greater automation has been slowly creeping into weapons with each successive generation for the past 70 years. As with automobiles, where automation is incrementally taking over tasks such as emergency braking, lane keeping, and parking, what might seem like a bright line from a distance can be fuzzy up close.

Where is this creeping autonomy taking us? It could be taking us to a place where humans are further and further removed from the battlefield, a place where killing is even more impersonal and mechanical than before - is that good or bad? It is also possible that future machines could make better targeting decisions than humans, sparing civilian lives and reducing collateral damage. If self-driving cars could potentially reduce vehicular deaths, perhaps self-targeting weapons could reduce unnecessary killing in war.

Much of the debate around autonomous weapons revolves around their hypothesized accuracy and reliability. Proponents of a ban argue that such weapons would be prone to accidentally targeting civilians. Opponents of a ban say that might be true today but the technology will get better and may someday be better than humans.

These are important questions, but knowing their answers is not enough. Technology is bringing us to a fundamental crossroads in humanity’s relationship with war. It will become increasingly possible to deploy weapons on the battlefield that can search for, decide to engage, and engage targets on their own. Beyond asking whether machines can perform these tasks, we ought to ask if they should. If we had all of the technology we could imagine, what role would we want humans to play in lethal decision-making in war?

To answer this question, we need to get beyond overly broad concepts like whether or not there is a human “in the loop.” Just as driving is becoming a blend of human control and automation, decisions surrounding weapons engagement today already incorporate automation and human decision-making. The International Committee of the Red Cross (IRC) has proposed exploring the “critical functions” related to engagements in weapon systems. Such an approach could help to understand where human control is needed and for which tasks automation may be valuable.

There are some engagement-related tasks for which machines could undoubtedly be useful. Some decisions in war have factually correct answers: “Is this person holding a rifle or a rake?” It is possible to imagine machines that could answer that question. Machines already outperform humans in some benchmark tests of object recognition, although they also have significant vulnerabilities to spoofing attacks.

Some decisions in war require judgment – a quality that is currently difficult to program into machines. The laws of war require that any collateral damage from attacking a target cannot be disproportionate to the military advantage. But deciding what number of civilian deaths is “proportionate” is a judgment call.

It’s possible that someday machines may be able to make these judgments in certain situations if we can anticipate the specific circumstances, but the current state of AI means it will be very difficult for machines to consider the broader context for their actions. Even if future machines can make these judgments, we need to ask: are there some decisions that we want humans to make in war, not because machines can’t, but because they ought not to? If so, why?

These are not easy questions to answer. Technology is forcing us to rethink humanity’s relationship with war. The recent open letter criticized the slow pace of discussions at the UN. It’s true – compared to rapid advances in AI and machine learning, international diplomacy moves slowly. But there is progress: in the past three years, discussions at the UN have begun to explore these topics.

Some have proposed adopting a principle of “meaningful human control”. While this term has proved somewhat contentious internationally (no doubt in part because ban advocates keep equating it with a ban), the concept of focusing on the role of the human is catching on. Some states have put forward alternative concepts such as “appropriate human judgment” or “appropriate human involvement.” Regardless of the specific words used, the concept of articulating a principle of “______ human ______” in war seems to be gaining traction. This is a new paradigm; instead of focusing on the weapon, it focuses on the human.

There is a lot of value in a human-centred approach to thinking about the role of autonomy in weapon systems. Technology is constantly evolving, but humans stay the same. The risk in focusing solely on what automation can or cannot do today is that such an approach could quickly become out of date. A human-centred approach to thinking about autonomous weapons could yield principles and concepts that could endure for years to come.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Artificial IntelligenceSee all

TeachAI Steering Committee

April 16, 2024

Darko Matovski

April 11, 2024

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

Allan Millington

April 10, 2024